Bonnets, Breeches and Brocade

05 Mar 2024

Fashion throughout history

By Tim Lowry

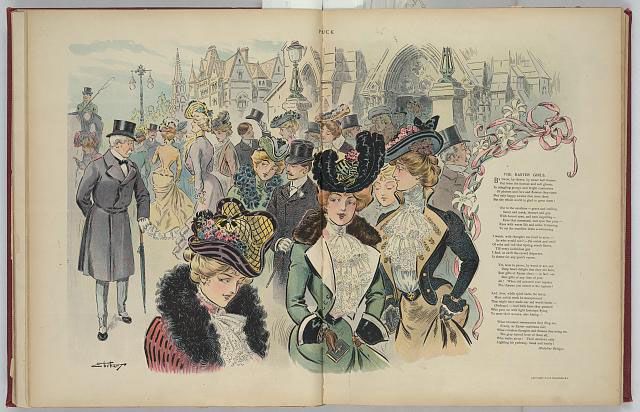

For as long as anyone can remember—which in Charleston is at least 300 years—the spring season has traditionally been a time for fashion. Little girls will appear in smocked frocks, bonnets and patent leather shoes. Their brothers will sport shorts, knee socks and saddle oxfords. The fathers will wear the traditional seersucker suit and foam skimmer hat that gentlemen have worn for over a century. However, there is more room for personal style among the ladies. Choices include pastel colored suits, floral dresses with just the right amount of flounce in the skirt, or more conservative monochromatic outfits accessorized with a bright scarf. However, the hat, which should not be wider than the shoulders, must definitely make a statement.

And how will a Charleston family know when to appear in all this spring finery? Some people might argue that a true, native- born Charlestonian simply has an instinct for such things. But if you are from off and need guidance, you’ll find a chart in the Book of Common Prayer that will help you pinpoint the exact date. Basically, on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox, Charleston families will attend Easter services dressed in the latest spring fashions. Many of these churchgoers will be seated in pews that were once occupied by fashionable ladies and gentlemen from Charleston’s Golden Age.

In the mid to late 1700’s, ladies of fashion did not choose a new dress from a catalog or scroll endlessly through online photos. Instead, “fashion babies”— dolls dressed in the newest model—were sent over from London and displayed in the finest shops. The sacque dress was extremely popular. The tight bodice was stiffened with whalebone ensuring a small waist and erect posture. The attached sleeves were always turned up with extra wide cuffs to reveal a lace trimmed chemise that covered the elbows. The very full skirt was pinned up in every imaginable way to expose a fancy underskirt or petticoat. The basic rule was that if the overdress was solid then the underskirt would be patterned or floral and vice versa. In back, extra fabric hung straight to the ground from the shoulders in a dramatic sort of cape. It was not uncommon for such a frock to incorporate 12-14 yards of fabric plus a few yards of ribbon, lace, braid and cording. A finished gown could weigh as much as fifteen pounds.

And then of course, the dress had to be accessorized, both above and beneath. According to historian Edwin Tunis, during the reign of King George III, fine ladies began pulling their hair up into “towers” that were held in place with liberal amounts of flour paste. The sculpted hair was powdered and decorated with false curls, feathers and ribbons. However, no amount of decoration could deter the occasional weevil from making a temporary home in the flour paste.

Shoes were made of soft leather with a pointed toe. Patterned silk was also popular. However, with the ridiculous amount of mud and manure in the streets, ladies commonly wore wooden clogs to protect their fine slippers. If one were to go out into the street minus the clogs, then it was said that a forgetful lady had appeared “slip shod,” which was a social faux pas.

Gentlemanly Garments

Not to be outdone by the ladies, a gentleman of the same era cut quite a figure and was the epitome of what one might call a “dandy.” His suit was in three pieces: breeches, waistcoat and a long coat. The breeches were knee length. Sometimes called “plus fours,” as the cuff fell four inches below the knee. They were often fashioned from imported silk. Italian, water-marked moire was common. The breeches were complimented by “clocked” stockings that displayed a fancy woven pattern along the side of the lower leg or ankle. The waistcoat, made from a rich brocade, was very long, extending below the waist much like an apron. The pockets held a gentlemen’s handkerchief, his snuff box, a few coins, a pin knife and a clay pipe could be thrust through a button hole. Over all of this was the long coat, which provided every opportunity for ostentation. The cuffs, much like the ladies’ sacque dresses, were turned up a full twelve or more inches to reveal cascades of lace that were attached to the billowing sleeves of the undershirt or “lawn.” The bottom half of the coat was practically a full skirt—not unlike a peacock’s tail—with ample yardage to display gold braid trim or even finer ribbon embroidery. The entire ensemble was even further decorated with an excessive amount of buttons. Made from coin silver, this was a way to wear your money on your sleeve displaying your wealth for all the world to see.

Hair Hierarchy

Where ladies tended to sculpt and powder their natural hair, men commonly wore wigs. The stylings were endless and included the peri, grizzle, campaign, ramillies, bob, brown and bag. The quality of the hair was a sure sign of social status. The lowest classes could only afford a wig made of goat hair. Middle class heads wore human hair. The upper crust sported imported yak hair, which was most desirable as it held curl better than inferior fibers. The wig maker created a gentleman’s headpiece on a wooden form that was carved to mimic the size and shape of the customer’s pate. This wig stand was commonly known as a blockhead. Well-dressed gentlemen no longer wear wigs, but the common derogatory terms “old goat” and “blockhead” stem from this long-abandoned fashion trend.

Unlike the ladies’ delicate slippers that were hidden by full length skirts, a gentleman’s footwear was highly visible. Consequently, shoes were made of leather and fastened with ornate, silver buckles. It was not uncommon for a popinjay of slight stature to wear high-heeled pumps fashioned from dyed leather or silk brocade.

In the late eighteenth century Charleston, these were the fashion basics. Not to mention hats, bonnets, handbags, walking sticks, parasols, swords, pistols, brooches, pins and rings, which were all carefully considered accessories to complete one’s outfit.

Fortunately, modern taste has simplified things considerably.

Storyteller Tim Lowry is a Southern raconteur from Summerville. Learn more at www.storytellertimlowry.com.