Treatment for Abnormal Heart Rhythms

19 Jan 2015

By DAN CONOVER

Tim Makuakane spent years wondering whether the surgically implanted electronic device that stood guard over his once-failing heart would ever do him any good. After all, in the decade since a mysterious coronary ailment almost killed him in the mid-2000s, a series of lifestyle changes had restored his heart to healthy function.

“There was a point where I was wondering, ‘Why do I even have this device in me?’” Makuakane said.

He got his answer in September – delivered by a shock that felt like a kick to his chest by an angry donkey.

Makuakane was in many ways an unlikely candidate for that lifesaving jolt – too young at 57, unburdened by coronary heart disease. Yet his story symbolizes the unfulfilled yet rapidly expanding promise of a relatively young branch of cardiology – coronary electrophysiology. The science behind treating deadly arrhythmias is on a rising trajectory in the 21st century, and advances in technology are driving an expansion of treatment options.

Yet even in Charleston, with some of the finest hospitals and best specialists in the state, the majority of patients who might benefit from devices like Makuakane’s implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (or ICD) still go undiagnosed.

Makuakane was one of those misdiagnosed patients back in 2005, until a fill-in doctor spotted something worrisome in symptoms his usual physician had originally written off as acid reflux. An ultrasound revealed that his Ejection Fraction (or EF) – a measurement of the heart’s pumping efficiency – had dipped to the 35 percent danger threshold. More tests revealed his heart was easily prone to slipping dangerously out of rhythm.

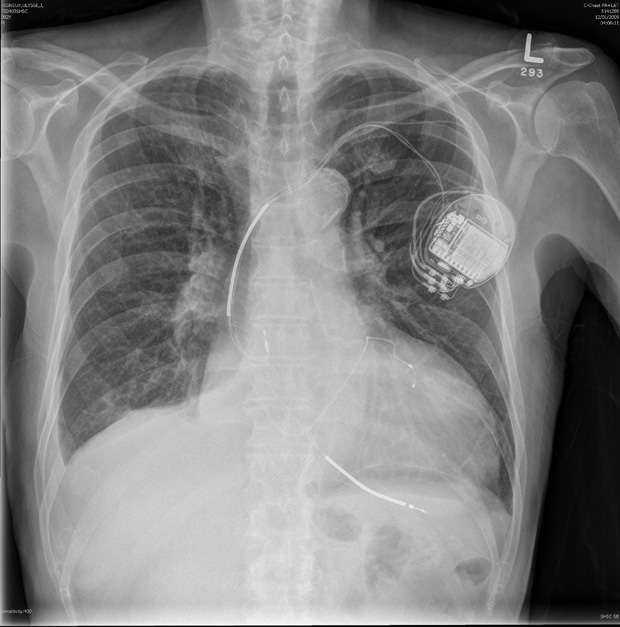

His cardiologist, Dr. Michael Gold, professor at the Medical University of South Carolina who specializes in coronary electrophysiology, prescribed him an ICD. It’s a small, programmable device ― implanted under the skin but outside the rib cage ― that serves a dual purpose.

If the heart starts beating too fast or two slow, the ICD acts like a pacemaker and attempts to restore its contractions to a normal, healthy rhythm. But if pacemaking fails, the ICD acts like an Automated External Defibrillator (or AED) ― think paramedics charging up those electric paddles on television medical dramas. The tiny implanted device recognizes a life-threatening event and automatically delivers an electric shock to jolt the heart out of the dangerous pattern.

AEDs have become far more ubiquitous in the past decade, but Gold said high-risk patients like Makuakane can’t rely on them. Studies indicate that implanting ICDs reduces mortality rates in likely candidates by 30 to 35 percent, he said.

Makuakane’s original ICD from 2005 initially shocked him too frequently, he said, but doctors customized its programming to match his natural heart function. He changed his lifestyle, too, eventually improving his Ejection Fraction to a healthy 57 percent. Other than a replacement device installed in 2009, Makuakane’s ICD seldom required any thought or attention.

Until this past fall.

As he remembers it, Makuakane’s brush with death came on a rainy yet otherwise unremarkable morning, in the midst of a mundane commute through Goose Creek to Santee Cooper. He hadn’t a clue that his heart had begun a cascading failure toward an event cardiologists call Sudden Cardiac Death.

Data collected by his ICD now tells doctors that Makuakane’s heart had quietly accelerated to 300 beats per minute, prompting the device to gently guide it back into a safe rhythm. The attempt failed, switching the ICD into emergency mode. It automatically delivered the first of two electric shocks that would ultimately blast his heart out of its quivering death spiral.

“The event was a ventricular fibrillation, which is the most dangerous of heart rhythms,” Gold said. “If not taken care of almost immediately it will be almost uniformly deadly.”

Just a few years ago, Makuakane’s survival would have hinged on one question: How many minutes would pass before someone arrived to apply an external defibrillator to his chest? The tyranny of time would not have been on his side. A patient’s chance of survival from a ventricular fibrillation drops 10 percent every 60 seconds, and even with a lifesaving AED intervention several minutes into a crisis, the damage to the heart is often life-changing.

Instead, Makuakane’s ICD shocked him within 15 seconds ― so early in the crisis that he hadn’t even noticed any symptoms. One moment he was driving, Makuakane said, and the next “it was like someone took a softball bat and hit me right in the chest with it.” It’s not a pleasant experience, but instead of losing consciousness while driving, he finished his trip to work uneventfully, spoke to the staff nurse, and arranged a ride to MUSC. His prognosis is good.

Advances in the field have made happy outcomes like that more common, said Dr. Darren Sidney, a coronary electrophysiologist at Trident Medical Center.

“Basically, it used to be that you had to die in order to get a defibrillator,” Sidney said. “You had to have sudden cardiac death and survive it in order to say ‘This person’s at ultra-high risk.’ It’s gotten a lot easier for a person with heart disease to get a defibrillator. I tell them it’s an insurance policy.”

Technology and technique go hand-in-hand, Sidney said, but the importance of research and development in the medical device industry shouldn’t be understated. In addition to ICDs and the ongoing trend toward miniaturization, cardiologists now have access to 3D mapping, contact-force-sensing ablation catheters, leadless pacemakers, long-life micro-batteries and invaluable patient data uploaded by Wi-Fi connection directly from implanted devices.

Yet that doesn’t mean everyone who might meet the protocol for an ICD even finds out about the option. Makuakane’s case, for instance, fell outside the obvious high-risk groups that would alert a physician to the possibility that his conditions signaled something more serious. His heart problems ― which were likely brought on by a virus ― were simply misdiagnosed by his family doctor.

Gold now finds himself advocating for increased access to implantable devices. Granted, they’re not for everyone ― only about 10 percent of patients with heart disease would meet the risk protocol for an ICD, he said. Yet only 30 to 40 percent of patients who would benefit from an ICD are actually getting the devices.

Two thirds of candidates for implantable devices suffer from coronary artery disease ― the build-up of plaque inside arteries that restricts blood flow. Other factors include previous heart attacks, high blood pressure and diabetes, alcohol or drug abuse, viruses and genetic predisposition. But generally, anyone from those groups with an Ejection Fraction of 35 or less is a candidate.

It’s mostly about education, Gold said. “People are attuned to their cholesterol numbers, their blood pressure, as measures of their health. They need to be aware of their EF, too.”

Makuakane’s EF was down to 37 after his September crisis, and he’s focused on boosting that back to the healthy range. But he no longer questions whether his ICD ― he calls it his Guardian Angel ― is still necessary.

“If it hadn’t been in me, I pretty much would be dead,” he said. “I feel like I got a second chance, so I want to do the right things. I have two sons and three grandsons. Now I think maybe there’s a reason for me to be here.”

Get to Know Your EF

Blood pressure? Cholesterol? Triglycerides? Check, check, check. Modern medicine generates a series of standard measures. Keeping track of your numbers can lead to better decisions ― and a healthier, longer life.

But when it comes to heart disease patients, it's time to add a new number to that list: Ejection Fraction, or EF.

“I usually tell heart patients that knowing your Ejection Fraction is like someone with diabetes knowing their blood sugar,” said Dr. Darren Sidney of Trident Medical Center. “If you have heart disease, you should know what your EF is, and if it’s less than 35 percent, you should be on a defibrillator.”

Clear enough. But what the heck is it?

Simply put, it’s a measurement of how much of the blood in the heart’s left ventricle chamber is pumped out with each contraction. A healthy EF is between 50 and 70 percent. An EF of more than 75 or less than 35 is cause for concern. Cardiologists can use several methods to measure EF, but ultrasound “echo” imaging is the most common.

EF is a good indicator of heart health ― but that doesn’t mean that every heart patient with an EF in the healthy range is out of the woods. Dr. Michael Gold of MUSC points out that if your heart has been scarred by previous events, it’s still at risk of Sudden Cardiac Death even with an EF above 50. But regardless of those factors, Gold said, “they need to be aware of their EF.”