Freedom through Song

04 Jan 2023

Harriet Tubman’s powerful melodic move as commander of the Combahee River Raid

By Tim Lowry

Music will forever be linked to the African-American experience and I can think of no story that serves as a more dramatic illustration of that than during the Combahee River Raid on June 2, 1863, led by none other than Harriet Tubman.

In the fall of 1861, United States troops arrived in South Carolina along the shores of Beaufort County and Port Royal Sound. After establishing a firm foothold in the heart of the plantation river country, the military, government officials, and many volunteers were able to establish the very first Reconstruction efforts in the American South, even as the war raged on in other parts of the country.

One of the most notable volunteers to lend aid during this time was none other than the celebrated “Moses of Her People” Harriet Tubman, the famed conductor of the Underground Railroad.

Her heroic acts were well known. After freeing hundreds of enslaved people and living under the constant threat of a “dead or alive” bounty price on her head, it would have been reasonable for Harriet to stay as far away from secessionist territory as possible. However, she had a calling to the people still suffering under the dark shadow of bondage and was not willing to just sit and wait for a war that might drag on for some time to eventually free her people. Freedom was needed now.

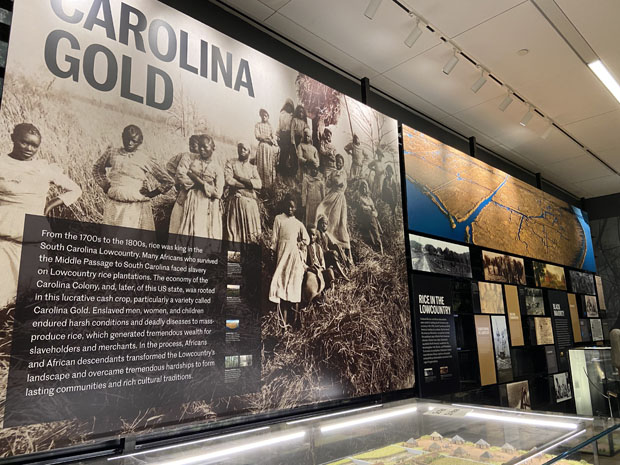

Beyond the coastal region that was firmly in the control of Federal troops were thousands of enslaved families still struggling under plantation task masters who were supporting the Confederate cause with supplies, food stuffs, and financial backing.

The coastal waterways surrounding these vast tracks of rice and cotton provided natural barriers to keep these enslaved families from making a run toward Beaufort and the protection offered them by the United States government. The Combahee River (referred to by some as the Jordan River) was such a barrier. A raid up the Combahee would serve a double purpose— it would free a significant number of slaves and at the same time, by removing is workforce, cripple the planters' ability to help finance the rebellion.

Using her unparalleled skill to network with local people, both free and enslaved, Harriet managed to gather a significant amount of information about the local area and the position of Confederate guns and river mines guarding the plantations along the shores of the Combahee River.

When General David Hunter asked her if she would guide several gun boats up the Combahee, Harriet agreed under the condition that Col. James Montgomery (a committed Abolitionist) be appointed commander of the expedition.

Years later, Harriet described the scene to a biographer: Frightened workers leaving the fields and taking to the woods. At sight of the gun boats, they would reappear among the trees to peer out, startled, and then run away at the sound of the steam whistle.

Freedom was at hand, all they had to do was run toward the waiting boats and yet, they hesitated. It turns out, the river was as much a psychological barrier as a physical one.

After living under slavery for many generations, it was hard for the plantation families to know whether or not this was a legitimate rescue effort or some sort of trick. However, Harriet Tubman was not the only African-American with excellent networking skills. Very rapidly, news of her presence and of the true nature of these fearsome boats carrying guns of war spread by word of mouth from group to group. And then, almost as if on a signal, more than 750 people rushed across the fields toward the riverbank.

Harriet recollected seeing a woman with a pail, rice smoking, just as she had taken it from off the fire. Another woman carrying twin children. Pigs squealing, chickens squawking, children crying, people shouting. In quick time, the shore was teaming with men, women, and children yearning to be free. Small boats were put out to carry everyone to the waiting gun boats in the middle of the river.

But in the mayhem and confusion, the overexcited crowds threatened to swamp the transports. Fearful of being left behind and unwilling to wait for a second or third trip, the desperate fugitives clung hard to the sides of the boats. Col. James Montgomery shouted to Harriet, “Get your people under control!” Laying aside her right to be offended at such a condescending tone, Harriet began to sing.

Experience had taught her that panicked people could not be ordered to be calm and quiet. She knew that it was through song that enslaved families had maintained hope and promoted calmness of spirit and presence of mind in frightening, dark, and desperate situations. She lifted her voice and began to sing.

“Of all the whole creation in the east or in the west, The glorious Yankee nation is the greatest and the best. Come along! Come along! Don’t be alarmed. Uncle Sam is rich enough to give you all a farm.”

The scene quickly calmed and more than 750 people were taken aboard the boats in an orderly fashion and transported to Beaufort, SC for their first taste of freedom. Additionally, significant infrastructure supporting the Confederate army was burned and destroyed as rebel defenders abandoned their positions and moved further inland.

Some accounts report that in the scuffling turmoil, Harriet Tubman’s dress was nearly completely ripped away from her body. She later dictated a letter to some of her supporters from the North asking them to send her a “bloomer dress made of coarse, strong material, to wear on expeditions.”

However, the former slaves gathered the following morning for a brief ceremony celebrating the success of the raid and their newly-won freedom. They immediately clothed their deliverers, both Col. James Montgomery and Harriet Tubman, with honor and glory as a spontaneous song was lifted and carried throughout the crowd, “There is a white robe for thee!”