Off to the Races

05 Jan 2021

Hampton Park once offered the finest horse racing in the South

By Suzannah Smith Miles

“I believe there is a few who now & then go to Church,” wrote Timothy Boardman, a Vermonter visiting Charleston in the year 1788, “but by all Observation I have been able to make I find that Horse Racing, Frolicking… [and] Gaming of all Kinds… to be the Chief Business of their Sabbaths.”

It has often been said that Charlestonians are, shall we say, obsessive, when it comes to ancestor worship. Indeed, in some elite circles “who you are” is not as important as “who your people were.”

Yet when it comes to impeccable ancestral bloodlines, nothing quite tops following the pedigree of a thoroughbred horse.

This kind of “horse sense” is as vigorous today as it was 300 years ago when the first formal horse race was held in Charleston.

“Charleston had a long a history of horse racing,” says author Kevin R. Eberle in his book, A History of Charleston's Hampton Park (History Press, 2012.) “Wealthy planters raised, traded, bought and even imported thoroughbreds that were raced both in Charleston and at other places in the Southeast. The first horse race in Charleston occurred in 1734 at a temporary course near a public house with a saddle and bridle worth twenty pounds as the prize. By 1735, the York Course was the first permanent track in Charleston and races were held each year, normally with a prize of a silver trophy worth about £100.”

It was also in 1734 that Charleston ranked another “first” with the formation of the South Carolina Jockey Club, the oldest such organization in the United States.

The first track, the York Course, was near the Quarter House Inn on the Charleston Neck and served as the main racing venue until the 1750s, when it was decided to build a new track closer to downtown.

This New Market Race Course, named after the famed course in England and located on what was then the edge of town (between Line and Huger streets and King and Meeting) hosted its first race in 1760. Afterwards, proprietor Thomas Nightingale offered stables and the annual “Charles Town Races” until the Revolutionary War. That war brought a halt to the sport and owners even hid their prize horses in deep swamps to protect them from being stolen by the British.

Golden Age of Horse Racing

Following the war, the sport began in earnest, ushering in what came to be known the “golden age” of horse racing in South Carolina.

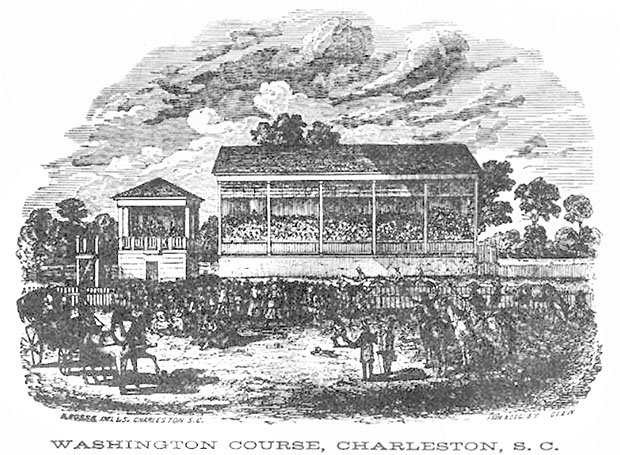

In 1791, a group of racing elite purchased a portion of Robert Gibbes’ Orange Grove Plantation and built the famed one-mile, oval Washington Race Course. This would be the epicenter for racing until the late 1800s. Today, we know this area as Hampton Park and the road circling the park, Mary Murray Boulevard, is built atop the original track.

“I believe there is a few who now & then go to Church,” wrote visiting Vermonter Timothy Boardman in 1788, “but by all Observation I have been able to make I find that Horse Racing, Frolicking… [and] Gaming of all Kinds… to be the Chief Business of their Sabbaths.”

Between 1792 to 1882, the Washington Course was known for offering the finest horse racing in the South. The highlight was Race Week, held in in February during the height of Charleston’s active social season. Along with daily races were elaborate dinners and private balls, including the exclusive St. Cecelia Ball and the Jockey Club Ball, held at St. Andrew’s Hall and which commenced at 11 o’clock at night and closed at 6 a.m. in the morning.

Race Week literally consumed Charleston’s social scene. Wrote artist Charles Fraser in 1843, “Schools were dismissed. The judges, not unwillingly, adjourned the Courts, for they were deserted by lawyers, suitors and witnesses. Clergymen thought it no impropriety to sese a well contested race; and if grave physicians played truant, they were sure to be found in the crowd at the race ground… The whole week was devoted to pleasure and the interchanges of conviviality; nor were the ladies unnoticed, for the Race Ball, given to them by the Jockey Club, was always the most splendid of the season.”

Says Kevin Eberle, “For seventy years, Washington Race Course came to boisterous life for a week in February, with racing on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. Tavern-keepers rented houses near the track to use as restaurants, bars and inns. Other entrepreneurs erected smaller structures. Ladies remained in the grandstand, but the gentlemen who roved among the nearby refreshment rooms or booths on the outside of the course mingled freely with gamblers, slaves, traveling salesmen, and others.”

William T. Porter, a well-known newspaperman and secretary of the New York Jockey Club in the mid-1840s wrote with admiration about Charleston’s racing society.

“The Charleston races are the most popular, the most fashionable and the best attended of any in the United States. Race week, in that city, has been aptly termed ‘the Carnival’ of South Carolina—the annual jubilee of the State. The reason is perfectly obvious; the course and its appointments are under the control of gentlemen of the highest character, and nothing is permitted to interfere with the legitimate sports of the Turf, which are managed with a degree of spirit, liberality, and scrupulous propriety unknown elsewhere on this side of the Atlantic.”

Formal Attire

Formality on all levels was the order of the day. Jockey Club rules were strict and if any rider “shall presume to cross, jostle, strike, or use any foul play whatever,” they were booted out and prohibited from racing again.

Other smaller racing groups like the Childsbury Jockey Club and the St. George’s Jockey Club in Dorchester had similar rules. No horse could start unless the rider was “dressed in riding Waistcoat, Leather Breeches, Leather Boots, or half Boots & a Jockey Cap of Silk or Velvet.”

With a constant view towards improving the breed, the Lowcountry brought in valuable importations of bloodstock from England and abroad. While owners and breeders were members of the elite, some of whom also rode their own horses, riders and trainers crossed all levels of society and were often enslaved African Americans. Still, social status took second place to talent and experience. Some slaves became respected trainers in their own right.

The loss of thoroughbreds during the Civil War coupled with the loss of plantations and ensuing economic decline eventually led to the demise of horse racing as it had been known. The Jockey Club disbanded in 1899, donating its assets to the Charleston Library Society. While horses did race on the track during the S.C. Inter-State and West Indian Exposition held between 1901-1902, the area eventually became city-owned Hampton Park.

One piece of this early horse racing history still exists, however. In 1903, the stone pillars from the original Washington Race Course were taken to New York and installed at the gates of Belmont Park, the home of today’s Triple Crown Belmont Stakes.