Pirates on the Prowl

04 Mar 2023

Charleston’s battle against the most notorious buccaneers in history

By Tim Lowry

Photo by Jenny Peterson

In May of 1718, Blackbeard, born name Edward Teach, the most notorious member of the “Brethren of the Sea” and the great terror of the Atlantic coast, anchored a small flotilla of vessels just beyond the Charleston Harbor. He began seizing and plundering ships attempting to enter and disallowing any vessel to leave without paying a high ransom. The city was in an uproar.

There had been a recent crime wave (excuse the pun) over the last several months. Pirates had become more and more brazen and something had to be done. However, Blackbeard was a formidable foe.

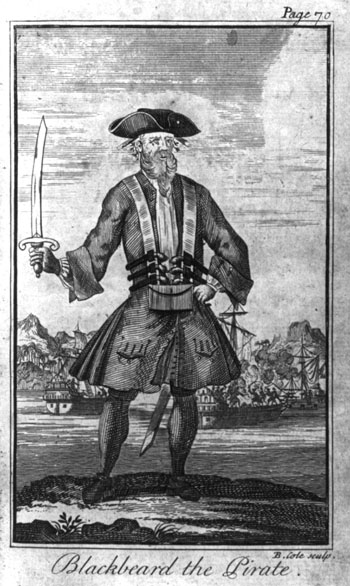

His penchant for cruelty, his almost superhuman strength, and his uncanny ability to outmaneuver any vessel that gave him chase were legendary. Capitalizing on this reputation, Blackbeard cultivated a particular style with nearly waist-length black hair done up in dreadlocks and a long beard to match. He was never seen without a double brace of pistols and a cutlass strapped to his enormous frame. He would often soak fuse cords in saltpeter and lime water, tuck the tassels beneath the brim of his hat, and light them on fire. When he turned upon a victim, the smoldering smoke gave him the appearance of a fire breathing dragon. (Eat your heart out Johnny Depp!)

Since its founding in 1670, the Colony of Carolina had maintained a degree of tolerance for the crime of piracy. The “dogs of the sea” were notorious for arriving in the port city with stolen goods claiming that the ‘untraceable property’ was found afloat on the ocean in an abandoned ship.

Most of the time, merchants were happy to buy the goods at a “steal of a price” no questions asked. If there were questions, the answers were vague statements like, “No living body aboard. Can’t be for certain, but the smallpox is a terrible scourge.”

Sly businessmen would simply promise to say a prayer for the deceased, and then without another word, would resell the goods at a significant profit. Of course, everybody knew the captain and crew aboard the ship in question had been attacked, plundered, stripped and then set adrift in a small boat, marooned on a lonely island—or worse.

Eventually, these shady deals taking place in the backrooms of sea shanty taverns caught the attention of the Crown. Rather than coming down hard on crime, the King agreed to look the other way as long as the pirates were sacking vessels from Spain, France, or the enemy of the moment.

To give this activity an air of legitimacy, the pirates were dubbed “privateers” and undoubtedly a percentage of profits was collected to benefit the growing British Empire. (Leave it to the government to find a way to turn armed robbery into taxation. But nevermind, we would deal with that at a later period in American history.)

This situation may not have been ideal, but it was simply the way things were done until Blackbeard managed to capture The Crowley, a passenger vessel bound for London.

Lo, one of the people on board was none other than Mr. Samual Wragg, a prominent citizen and member of the Council of the Province of Carolina. And a bonus—Mr. Wragg was accompanied by his four-year-old son, William. The father was a prize, but the boy would make a very valuable bargaining chip.

Blackbeard sent a small boat into Charleston with demands written in a letter to the Colonial Government. Not every pirate was literate, but Blackbeard was rather proud of the fact that he could read and write and undoubtedly signed the document with a flourish. He demanded a chest of silver. He also required an additional chest of medicines as several of his men were suffering from what some call “the French disease.” He made it clear that his intentions were to wait only for a limited time and then if his demands were not met he would begin murdering prisoners and threatened to start with the four-year-old boy.

The governor’s council agreed to the demands and Samuel Wragg and the other passengers were returned to the city, but only after they had been stripped nearly naked.

Blackbeard and his crew, dressed in the stolen fine array of Charleston gentlemen, sailed over the horizon with enough plunder to retire to a life of idol luxury on a small Caribbean island. Some sources say that he made off with more than 1,500 pounds sterling ($400,000 today) from Samual Wragg alone.

This brazen act of terrorism motivated the Colony of Carolina to put an end to the piracy problem once and for all. However, Blackbeard would avoid capture. Consequently, other sea dogs were apprehended, swiftly tried, and condemned. In another time and place, these “lesser criminals” might have fared better, but our dander was up.

Pirate captain Steve Bonnet, though far from completely innocent, suffered guilt by association with the notorious Blackbeard as did another scoundrel by the name of Richard Worley. Worley was killed in a battle near Sullivan’s Island, which may have been a mercy considering that Steve Bonnet, his crew of 29 men, and all 19 of Worley’s crew were hanged at the tip of the Charleston peninsula. Their bodies were publicly displayed as an example to anyone contemplating such a life of crime. This determined effort by the governor’s council to end terrorism in the Charleston harbor resulted in a world record—the most pirate hangings in a 30-day stretch.

Blackbeard, on the other hand, managed to make even his death the stuff of legend as he was slain in battle on November 22, 1718. The governor of Virginia had a price on his head. Since that’s all the governor was paying for, that’s the only part of him his executioners took back to Virginia.

They sailed into port with the huge, hairy visage hanging from the bowsprit of their ship. Blackbeard’s countenance announced the end of an era and his name was immediately and forever synonymous with what came to be known as “The Golden Age of Piracy.”

Storyteller Tim Lowry is a Southern raconteur from Summerville. Learn more at www.storytellertimlowry.com.