Those Who Watched Over Us

02 Jan 2019

Meet the men who formed the first line of defense in Colonial Carolina

BY SUZANNAH SMITH MILES

They were a breed apart, men who preferred the wilderness to life in town. Called coastal scouts or watchmen, they were the backbone of an important colonial first-alert warning system that stretched the entire coast, from Cape Romain to the Savannah River.

They were rough, tough and made of the hardy stuff that creates either scoundrels or heroes, and sometimes both. From their forlorn outposts set on windswept barrier islands, they were a vital first line of defense for Charles Town during the late 1600s and early 1700s, ready to sound the alarm at the approach of an enemy fleet, specifically the Spanish in St. Augustine.

This was no idle threat. Charles Town was then still a tiny colonial settlement and, as far as the Spaniards were concerned, the English were trespassing on lands Spain had claimed a century earlier. The Spanish made three forays against the Carolina colony prior to 1700. All three attempts failed, largely as a result of the alarms raised by coastal watchmen.

While these hardy men might be described as the ultimate outdoorsmen—the kind of guys who preferred a life in the open wilds—most weren’t the kind of fellows you’d feel good about taking home to meet the folks. One who described them vividly was Colonel John Barnwell (1671-1724) of Beaufort, who called them a “wild, idle people” who may have known how to hunt the forest or fish, but that “Scarce One of Them but understands the Hoe, the Axe, the Saw, as well as their Gun and Oar.”

They also had a tendency towards drunkenness and Barnwell wrote how they were “continually Sotting” and “ready for the Rum on the least disguise.” Despite these flaws, Barnwell respected their importance to the colony. “They are greatly useful,” he wrote, “if well & Tenderly managed.”

Barnwell was of a different stripe himself. He’d come to Carolina as a young man in 1701, leaving a life of privilege in Dublin merely, as one family friend later wrote, “out of a humor to go and travel but for no other Reason.” When this progenitor of the distinguished Lowcountry Barnwell family was granted over 6,000 acres of plantation land near Beaufort, he was settling in an area as wild and untamed as any in the New World.

Barnwell quickly became prominent in early Carolina affairs and served as the colony’s deputy surveyor general. Yet by necessity Barnwell had to be as rugged as the scouts and watchmen his safety depended upon. He was a natural leader who knew how to manage men, although it is doubtful if he did so “tenderly.” He earned the nickname “Tuscarora Jack” for successfully leading a group of men (including fighting braves from South Carolina tribes) against the warring Tuscarora Indians in North Carolina in 1715.

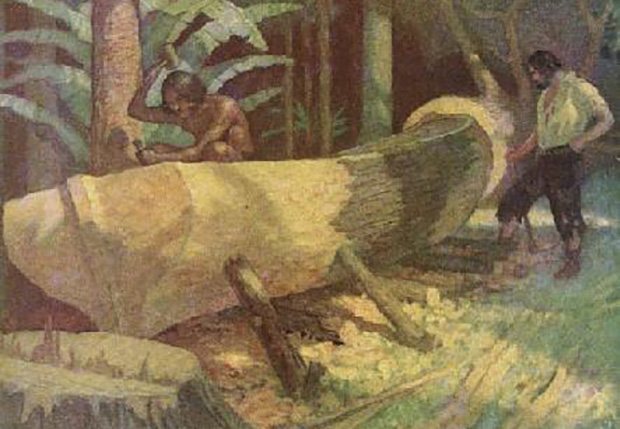

The need for scouts and watchmen came onto the scene as early as 1686, when the Grand Council ordered that beacons and watch towers be erected “in the most convenient place in sight of one another from Charlestowne to the south side of the south entrance of Edisto River, and from thence to the North side of Westoe [Savannah] River.” These lookouts were crude affairs, wooden towers from which they could fire a cannon or light a beacon to warn of approaching vessels. Each was manned by a watchman and two members of the coastal Native American tribe in that particular area. Getting to and from these outposts was done by boat and the most common watercraft used by the scouts was a type of canoe called a pirogue (or piragua), similar to the Indian dugout canoe.

It was a clever system. By using fires and cannon shots as signals, news of an invading fleet could quickly be communicated from one island to the next, eventually reaching Charles Town. Almost every one of the South Carolina barrier islands had at least one watch tower during this period of history, sometimes one at each end of the island.

The most significant, and certainly the longest lasting watch on the coast was the lookout on the southern end of Sullivan’s Island under Captain Florence O’Sullivan, for whom the island was ultimately named. Like Barnwell, O’Sullivan was a man of means and status and O’Sullivan was particularly important because of his military background. Yet unlike Barnwell, O’Sullivan was difficult to work with and thoroughly disliked by many.

Colonist Stephen Bull called O’Sullivan “a very troublesome person” who was “daily complained of for ill actings.” The great humanist John Locke, secretary to Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper, went further, describing him as, “dissentious, troublesome… knavish, disliked, unfit.” He even used the colloquial put-down of the time, calling him an “ill-natured buggerer of children... a very ill man." Despite this reputation, O’Sullivan was good at his job. It was O’Sullivan’s watch that alerted the colony when the Spanish launched their unsuccessful attack against Charles Town in 1686.

By the 1720s, the colonists faced not only threats by sea but by land from warring Native American tribes. Thus new requirements were added. In 1725, the eight watchmen assigned to the outpost at Pon Pon (the Native American word for the North Edisto River at present-day Jacksonboro) were required to not only have a horse “and accoutrements” but be armed with “a gun, a pistol, cutlass or hatchet, powder-horn with at least a quarter of a pound of powder and cartouche box, with twelve charges."

Their watch also introduces one of the first historical references to the use of a guard dog in South Carolina. It was ordered that “to prevent the said scouts from being surprised by Indians, by day or by night and for the better discovering and finding out where the said Indians hide and lurk… every one of the said eight scouts shall find and provide a large mastiff or mungrel bred dog, to go constantly along with them in their scouting."

Despite their contrariness and attachment to strong drink, the early scouts were able frontiersmen. With a dog, a gun, Indian companions and a bottle of rum, they stood watch. Their names may be lost to time, but their vigilance helped the settlement at Charles Town succeed.