Let Us Entertain You

06 Nov 2017

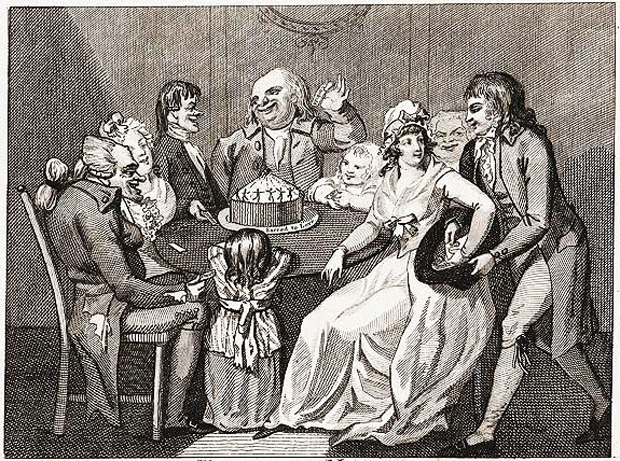

The art of entertaining our guests for fun or political gain has been handed down since the 1700s

By SUZANNAH SMITH MILES

The season is upon us with the flurry of cocktail parties and often lavish entertaining that marks the Charleston holiday season. The enjoyment of opening our doors (and liquor cabinets) to heavenly hosts of thirsty company is as old as the city. “Let us entertain you” could easily be the Charlestonian’s mantra. Entertaining is one of the most delightful aspects of Charleston’s reputation for hospitality.

Thus, if you care to “entertain” the idea, read on. Here’s a ramble through a few entertaining parts of Charleston’s entertainment history. Not surprisingly, most revolve around Charleston’s love for potent potables.

We begin in March 1735, when a brewer named Daniel Bourget advertised that he could provide folks with fresh malt ale. It was “strong, middling and small beer,” and “good entertainment” for his patron’s horses. Ostensibly, while his customers happily quaffed his craft brews, their entertained horses (which meant they had been stabled, fed and watered), neighed approval.

Bourget was also Charles Town’s premier baker (there is more than one way to use yeast). By 1739, the influx of new bakers settling in town began cutting into his profits. Bourget’s solution? He suggested to the other major baker in town, George Helm, that the two slash the cost of their bread, assuring the good townspeople they were doing so to keep the newcomers from scalping them with unreasonably high prices.

Alas, Helm spilled the proverbial tankard and admitted that Bourget’s true purpose was to drive out the competition. The real plan was price fixing. Once they had cornered the market they’d push up the prices even higher than before.

Since Helm died shortly thereafter, perhaps he made this confession so he could meet his maker with a clear conscience. Yet the business of entertaining apparently remained in his family. When his widow died in 1747, among her effects were 84 gallons of Maderia wine and 102 gallons of rum.

With that much booze on hand, she likely operated a “house of entertainment,” the term generally given to an inn, pub, or “long room” like McCrady’s or Shepheard’s Tavern where people enjoyed their libations around one extremely long table.

In later years, a house of entertainment began to take on racier connotations as some establishments not only offered patrons good Jamaica rum, but also the women who served it. Legend says there was once a bordello on the top floor of the Pink House, perhaps the oldest tavern in the city. Built in 1712 and located on cobblestoned Chalmers Street, when it was in operation this portion of the street was known as Beresford's Alley, notorious for its many houses of ill repute. The street did not become Chalmers Street until 1801, so named for Dr. Lionel Chalmers whose apothecary was located at the corner of Church Street.

As only can happen in Charleston, one Beresford Alley made room for a second one, the other running a block between King and Archdale Streets. This eventually became the center of the city’s red light district and, as late as 1945, there were 29 houses of “entertainment” in this vicinity.

The city ordered the brothels closed. To offset the area’s dubious reputation it was decided to rename the street. As members sat in city council chambers and pondered a new name, someone noticed the bust of inventor Robert Fulton perched on the windowsill. “Let’s name it after him,” came the suggestion—and it has been Fulton Street ever since.

Today, the Beresford name is largely seen on Daniel Island. There in the early 1700s, Richard Beresford, one of the richest men in all the colonies, built his mansion, predictably named Beresford Hall. It overlooked—what else—Beresford Creek.

Beresford died in the 1722 (curiously from a falling tree limb) leaving a vast estate, much of which was still intact when his grandson, Richard “Dick” Beresford III, went to London in the 1760s to study law at the Middle Temple. Here, while enjoying an unusual type of entertaining, he lost one of his eyes.

“I am six feet two inches high, without my shoes,” Dick Beresford wrote in a humorous self-description. “I have black hair, and large black eyes, or rather one large black eye, the other having been burnt out at flatdragon.” He also added that he had lost half his teeth, “knocked down my throat in an attempt to rescue a wife from her husband, who was ducking her in a horse-pond.”

The episode between the man, his wife and the horse pond may always remain a mystery. A bit of research revealed that it wasn’t a flatdragon that took out Beresford’s eye, it was flapdragon, a drinking game popular in England at the time. The object was to catch a lighted raisin out of a glass of burning brandy and extinguish it by swallowing it. Or, as described in DisRaeili’s Current Literature published in 1786, “Such were flapdragons… small combustible bodies fired at one end and floated in a glass of liquor, which an experienced toper swallowed unharmed, while still blazing.”

Beresford apparently wasn’t very proficient at flapdragon. One shudders to think of losing an eye to a flaming raisin. It does prove that young men away at college in Beresford’s day were just as mindless about their drinking antics as they are now.

The loss of an eye was no hindrance to Beresford. During the Revolutionary War he served as General William Moultrie’s aide-de-camp, was a member of the Continental Congress and eventually became Lieutenant Governor. Among his friends was merchant and statesman Henry Laurens, which leads to a story about one of the Lowcountry’s most enduring entertainments: the barbecue.

The word is of Carib Indian derivation, "barbacoa" being their word for roasting meat over an open fire. It was likely brought to our shores with early Spanish explorers who, in turn, introduced it to the coastal Indians, who then shared the custom with the early colonists. The barbecue as a social event quickly became popular. Even in those early years, politicos were hosting barbecues as a way to solicit votes.

In 1768, Laurens wrote to a friend, "We are becoming Very important in this Town in the Electioneering business. Today a Grand Barbacu [sic] is given by a very Grand Simpleton, at which Members for Charles Town are to be determined upon… I walk on the Old Road, give no Barbacu nor ask any Man for Votes."

The “Grand Simpleton” Laurens was referring to was none other than Christopher Gadsden, one of Charleston’s staunchest patriots and designer of the famous “Don’t Tread on Me” flag. The barbecue mentioned was one of many gatherings of the Sons of Liberty, who met at Charleston’s Liberty Tree, a large oak in Mazyck's cow pasture (today’s Alexander Street, just north of Calhoun) where “many loyal, patriotic and constitutional toasts” were given. With 45 bowls of punch, 45 bottles of wine and 92 glasses, they raised their glasses to every patriot in Britain or America. The number 45 was in honor of English politician and radical, John Wilkes, who had gained fame for attacking unfair taxation in an article printed in Issue 45 of The North Briton.

Laurens may not have owned up to giving any barbecues, but he did confess to having racked up a sizable bill for "entertainments" during the elections at Dillon’s Tavern, a popular Charleston meeting spot on Broad Street. All go to prove that names can change and the years may come and go, but some things remain the same.