Sea Serpents and Other Oddities of the Sea

03 Jul 2019

Some Honest-to-Goodness Fish Stories from Charleston’s Past

By Suzannah Smith Miles

“On Wednesday morning last,“ reported the Charleston Sunday News on June 28, 1885, “a gentleman who by a strange coincidence or freak of nature is named Smith, was walking along the beach near Breach Inlet on Sullivan’s Island… when he saw a snake. Mr. Smith doesn’t often see a snake, but when he does it’s a daisy. This snake was nearly 100 feet long… Mr. Smith is not over six feet long himself, but whenever he sees a snake 100 feet long he does not shrink. When he saw this one he determined to make it all his own.”

The article was entitled “Mr. Smith and the Sea Serpent,” and the writer spared no ink when it came to description.

“It is plain that it was no common dime museum snake, but a genuine old aristocrat right from the swell part of the sea. He had a neck three feet in diameter which extended half his length… This snake’s head was like a lizard’s, and it had a single row of cone-shaped teeth which pointed backward. The body was eight or ten feet in diameter, and was provided with four flukes twenty feet long. These flukes were pounding the water with blows that sounded a good deal like the echoes of guns at Sumter ‘during the war.’ The snake’s eyes were as big as saucers and stood out about six inches from his head.”

The writer continued, very much tongue-in-cheek, to describe how Smith and two other men attempted to pull the sea creature ashore with a rope.

“With all the accuracy and grace of Texan cowboys they flung a lasso over the head of the sea serpent. Then they took the other end of the rope and proceeded suddenly up the beach. The next thing they knew there was a sharp report, like the last expiring gasp of the Fourth of July, and the dauntless three had plunged forward upon their sunburned noses into the pitiless sand. When they had regained their feet and had mined the sand out of their eyes, they turned and found that only a space of boiling foam marked the spot where the sea serpent had been. The rope had broken. Sadly and tearfully the three bent their steps homeward. The sea serpent had left them, and they would not be comforted. But as for Smith, he labored not wholly in vain, for he has some of the scales which the serpent shed in his struggle to escape, and he has the rope. The sea serpent has gone, but he is not forgotten.”

This wasn’t Nessie or the creature from the black lagoon. Mr. Smith’s “snake” was very real and likely the source of the many sea serpent tales of yore. It was a giant oarfish. The only fanciful part of this fish story was the 100-feet length. But then, Mr. Smith was a fisherman. The “one that got away” is always larger in the telling.

In late August 1900, two fishermen caught a similar “sea serpent” off the Charleston Battery much to the awe and glee of onlookers. The writer describing the event in the Evening Post was poetic: “The dragon was as long as a parallel of latitude. Its head was flat, its nose was red, its teeth were sharp, its tail was slit, its eyes were shining and its feet were like a devil’s or a politician’s.”

Indeed, there are many strange fish in the sea. What’s more, they are historically drawn to the deep waters of inlets. In January 1944, the Evening Post reported that a gigantic squid was found dead on the beach at Breach Inlet, “a strange creature… nature’s original rocket device.” The squid was such a curiosity it was taken to the Charleston Museum and put on display.

Inlets are a bit like a marine automat. Food comes in with every tide. There’s an ever-changing variety of options as all types and sizes of fish swim in and out with the current. This is the original “no such thing as a free lunch” setting, with bigger fish preying on smaller fish all the way down the food chain.

This also makes inlets a favorite haunt of sharks. Of such, this writer can attest. Once while crabbing at Breach Inlet, I gasped in horror as a tiger shark the size of a four-door Buick sedan swam lazily by, not twenty feet from where I was standing in the shallows. Needless to say, I pulled my toes out of the water.

That particular shark swam on unhindered. Not so the 15-foot, 1,000-pound tiger shark pulled from the surf at Kiawah in August 1913. The fisherman was W. E. Simmons, who was fishing for a mere channel bass when the shark hit. Described in the newspaper report as “a veteran angler and yachtsman,” Simmons had the skill and know-how to be able to land such a monster with a rod and reel.

While the tiger shark Simmons caught at Kiawah was sizeable, it wasn’t the biggest shark he’d seen. That prize went to a behemoth 25-footer he observed off the Isle of Palms being harassed by a school of porpoises, who eventually chased it into the deep. One wonders if this was the great-grandpappy of Luna, the massive great white tracked by Ocearch who’s been hanging around South Carolina waters in recent months.

The report that the porpoises were chasing the shark isn’t unusual. Porpoises and sharks are natural enemies and known to do battle. In July 1910, folks taking the trolley from Sullivan’s Island to Mount Pleasant over the Cove Inlet bridge (today’s “old Pitt Street bridge” in Mount Pleasant), watched a terrific aquatic battle between a big shark and a huge porpoise. The Evening Post reported, “From the cars could be seen a big fin and the lithe strong body of the shark whirling around lashing the waters in the fight with the hog porpoise. Old stagers say that the porpoise usually beats the shark in a fair fight, and this morning it was the case as the larger fish suddenly turned tail and swam away, leaving the stout purpose to finish the whiting over which the two monsters of the deep had presumably been fighting.”

When sharks do get their prey, it has been shown that they aren’t particularly known for having a finicky appetite. After an 11-foot tiger shark was caught in July 1860, the Courier reported that, “on being opened, the stomach was found to contain four king crabs—a lot of large bones, several pieces of salt beef, some lumps of clay and a LEATHER BOOT.” Luckily, the boot had not been attached to a foot but had been lost overboard by a harbor pilot the previous day.

Not so pleasant was what was found in an 8-foot shark caught from one of the Charleston wharves in August 1842. Its stomach was found to contain a red flannel shirt and a man’s hand “with only one fingernail.” No further explanation was given, or perhaps needed.

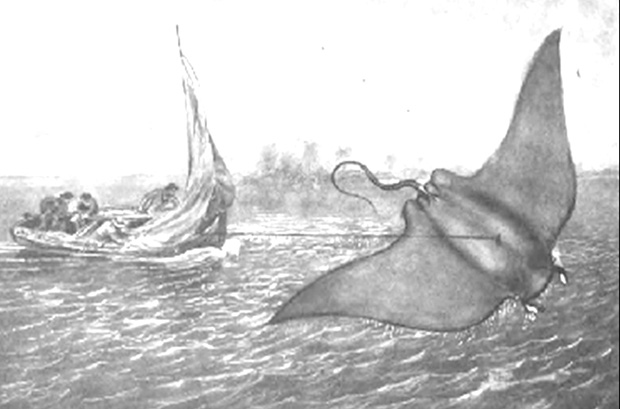

Sharks aside, there are a host of unusual creatures floating, swimming and chomping their way through Neptune’s realm. One finds everything from prehistoric sturgeons to needle-nosed gars in our Lowcountry waters—from pale blobby jellyfish to sleek shiny bluefish. The truly grotesque looking wart-faced, slimy- skinned toadfish continues to harass the fisherman on salt creek docks. We have eels and sting rays—even the majestic, mammoth ray called the devil fish that can spread out its wings and literally fly out of the water.

But, hey, it’s summertime! The living is easy. Fish are, indeed, jumping and drawing fishermen to boats, docks and beaches. There are fine specimens waiting to be caught which offer excellent sport and great eating—trout, flounder, whiting, the occasional blue marlin and Charleston’s absolute favorites, (ahem), porgy and bass. In the words sung by the blues singer Henry Saint Clair Fredericks, otherwise known as Taj Mahal, “I'a-goin' fishin', Yes, I'm goin' fishin', And my baby's goin' fishin' too!”