Shipwrecks and Gershwin

03 May 2019

Laid-Back History from the Edge of America

By Suzannah Smith Miles

Before the jetties were built in the 1880s, creating one deep channel straight into Charleston harbor, the main shipping channel came up from the South, running alongside Folly and Morris Islands. In those days, what was known as “crossing the bar” into Charleston harbor was not easy. What with bad winds and violent tides, a vessel could easily run aground on a shoal or be driven onto the beach. At Folly Island, this happened over and over again, especially in the days of sail. One can only speculate how many vessels were shipwrecked during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Those who survived these tumultuous trips could not expect much of a welcoming committee. Back then, the only residents were those who lived on a plantation on the island, first established in 1696 when William Rivers was granted 700 acres known as Folly Island. The plantation continued with various owners well into the 19th century. In 1825, when the land was for sale, an advertisement noted that the plantation grew vegetables for the Charleston market, harvested palmetto logs and used the gracious plenty of oyster shells for making lime to support the building industry. The main house was on the back of the island overlooking Folly River — generally the area beyond the dead end of West Indian and West Hudson. This residence was used in the winter; a house on front beach served as a cooler spot during summer months.

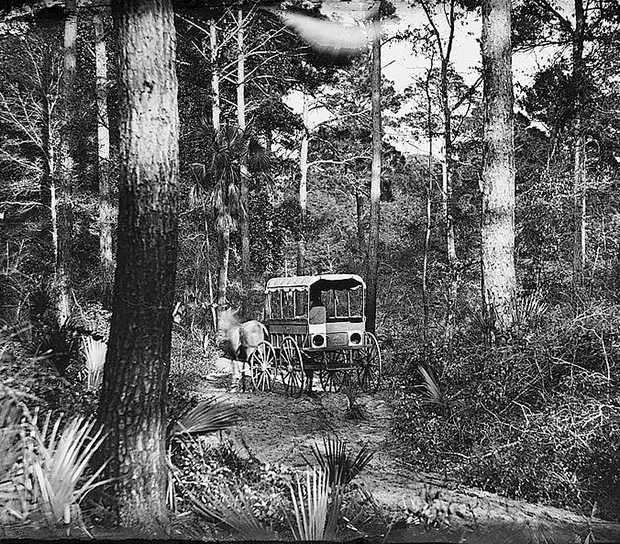

Living on a private island might sound idyllic to us, but it was no doubt a lonely existence. There were no roads and no causeways. No bridges. No neighbors. Only the windswept beach, the sound of the surf and miles of salt marsh separating the island from the mainland. Occasional incidents aside, nothing much happened in the area for years. In 1796, the Brig “Grampas” came ashore with a hold filled with wine — in hogsheads, pipes and quarter casks — and, rather amazingly, a cargo of elephant tusks. In 1810, a 69 foot whale washed ashore. The 1832 shipwreck of the Brig “Amelia,” stranding 108 people, was an event that became particularly ugly when an outbreak of cholera caused the island to become a quarantined area for months. In 1852, Peter Campbell, the owner of Folly at the time, drowned while sailing to the city. When his estate was put up for sale one year later, it included horses, cattle, one sloop and other boats.

Then, of course, came the Civil War, and this quiet, nearly forgotten island suddenly became a staging area for one of the greatest sieges in military history. By July 1863, there were nearly 11,000 Union soldiers encamped on Folly and its environs. For three months, they maneuvered to take Battery Wagner on Morris Island. Their endeavors were supported by a daily barrage of heavy metal from the largest American naval fleet assembled to that date — the Federal blockading fleet, which included armed ships, gunboats and monitors as well as the powerful steam frigate, USS New Ironsides.

It should have been an unfair fight. Wagner was a small fortification situated on a mere strip of sand and marsh, manned by only 740 Confederates from South Carolina, North Carolina and Georgia. Instead, it took 58 days — and 2,318 Union dead or wounded — before the Confederates were forced to evacuate Wagner the following September. The siege of the attempt to take this small but resolute fort was memorialized in the movie “Glory.”

The Union forces stayed on Folly and Morris Islands until the end of the war, and then life on the island returned to its usual peace.

By the 1890s, however, change was in the wind. Northern investors were beginning to look at the South Carolina and Georgia barrier islands as ideal locations for resorts. The success of the Isle of Palms, developed in 1898, turned many heads. Yet, a major reason the Isle of Palms had been so successful was because a ferry and trolley system linked the island to town. Meanwhile, the only way to get to Folly Island was on a boat. And, thanks to the advent of automobiles, people wanted a destination they could drive to — it was part of the allure.

Evolution commenced with the organization of the Folly Beach Corporation in 1918. “Good progress is being made in the Folly Island development project,” wrote “The News & Courier” on March 5, 1920, calling it “one of the most extensive and promising development undertakings launched in this section ….The island that was formerly nothing but waste territory is now undergoing a transformation, as well as the water passages and roadways between this beach and Charleston.”

Of the 630 lots which had been put up for sale, 500 sold almost immediately, and the issue of connecting the island with Charleston had been “vigorously attacked.” “Excellent progress” was being made regarding the building of roadways, causeways and bridges. On April 15, 1921, the paper reported that the first two-and-a-half story building was being built in the Folly Island business district. With that, island was changed forever.

Perhaps the most noted vacationer at Folly during these years was composer George Gershwin, who spent much of the summer of 1934 on the island writing his opera, “Porgy and Bess.” The simple cottage where he stayed must have been quite a change for the New York sophisticate, who was far more accustomed to luxury than to flies, gnats and mosquitoes, which, he wrote to his mother, left him with “nothing to do but scratch.”

Yet Gershwin was soon caught up in the allure of the island. Dubose and Dorothy Heyward were in a cottage right across the street. Visiting the then-rural James Island Gullah communities, Gershwin was introduced to the native language and music. Indeed, the living was easy, the fish were jumping and musical history was made.

By the 1940s, the front beach had become a destination unto itself. Cars from Charleston lined the beach in front of the Atlantic Pavilion, where the speed limit of 10 mph was strictly enforced. Even if you didn’t have a car, you could spend the day on the beach by taking the new bus line to the island from Charleston.

By the 1950s, the island was settled and immensely popular. The “Edge of America,” however, was crumbling away. The same jetties which opened the harbor to shipping had drastically changed, affecting the currents had on the shoreline. Both Morris Island and Folly were suffering catastrophic erosion. Even the “new” front beach houses were seeing high tides under their porches.

The building of groins and breakwaters helped stem the tide somewhat, but, by the 1970s, many of the houses along the front beach had been claimed by the sea. In some places, both Arctic and Atlantic Avenue were entirely washed away, the only remaining memory being the iconic Atlantic House restaurant until it, too, was claimed by the ocean during Hurricane Hugo in 1989.

Today, with the regular addition of billions of tons of sand, the beach is holding its own and the Edge of America continues to prosper. Real estate is booming, the restaurants are filled and the island’s popularity has not dimmed. Just as in Gershwin’s time, the “livin’ is easy” on this laid-back beach.